Osteoarthritis

Highlights

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease that typically affects joints in the knees, hip, hand, feet, and spine. It is the most common form of arthritis.

Risk Factors

- Older age. Osteoarthritis usually occurs in older adults.

- Women. Osteoarthritis occurs more often in women than in men (although among those younger than age 45, men are affected more often than women).

- Obesity. Being overweight increases the risk of developing osteoarthritis.

- Joint injuries. Sports injuries or occupational repetitive stress can lead to osteoarthritis.

Symptoms

Symptoms of osteoarthritis begin gradually and worsen slowly over time. Osteoarthritis pain is generally described as:

- Aching or stiffness

- Worsening during activity and improving when at rest

- Occurring intermittently

- Causing a grating sensation when the joint is moved

- Bony growths can occur on the margins of joints

Diagnosis

Osteoarthritis is usually diagnosed based on a physical exam and the results of x-rays. In some cases, the doctor may take a sample of synovial fluid from the joint.

Treatment

There is no cure for osteoarthritis, but treatment can reduce pain and improve flexibility, joint movement, and quality of life. Treatment options include:

- Lifestyle modifications and non-drug approaches such as exercise, weight loss, and physical therapy

- Medications, including mild pain relievers such as acetaminophen, corticosteroid injections, and hyaluronic acid injections

- Surgery may be considered for severe osteoarthritis that is not helped by other treatments

New Guidelines

In 2012, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) released updated recommendations for drug and non-drug treatment of hand, knee, and hip osteoarthritis. Key points include:

- The recommendations emphasize the early use of non-drug treatments, especially aerobic, aquatic, and resistance exercise. Overweight patients are encouraged to lose weight. While not strongly recommended, the ACR considers tai chi, acupuncture, and transcutaneous electrical stimulation (TENS) appropriate options for some patients.

- For patients older than 75 years old, the ACR recommends skin-applied (topical) NSAIDs instead of oral NSAIDs. For older patients, topical NSAIDs pose less risks for stomach bleeding and other side effects. (However, see Drug Warning below.)

- Topical capsaicin, a pain reliever derived from chili pepper, is recommended for hand osteoarthritis but not knee or hip osteoarthritis.

- The ACR does not recommend the use of glucosamine and chondroitin supplements.

Drug Warning

In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned that topical muscle and joint pain relievers can cause chemical skin burns in rare cases. These products contained menthol, methyl salicylate and, in a few cases, capsaicin. The FDA recommends not applying bandages or heating pads to areas treated with these products. If you see signs of blistering or burning, stop using the product and seek medical help. These warnings also apply to topical NSAID products that contain trolamine salicylate.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis, also known as degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of arthritis. In this disorder, a joint loses cartilage, the slippery material that cushions the ends of bones, over time.

As a result, the bone beneath the cartilage changes and develops bony overgrowth. The tissue that lines the joint can become inflamed, the ligaments can loosen, and the muscles around the joint can weaken. The patient feels pain and movement limitations when using the joint.

Joints

Joints provide flexibility, support, stability, and protection. Specific parts of the joint, the synovium and cartilage, provide these functions.

Synovium. The synovium is the tissue that lines a joint. Synovial fluid is a lubricating fluid that supplies nutrients and oxygen to cartilage.

Cartilage. The cartilage is a slippery tissue that coats the ends of the bones. Cartilage is composed of four components:

- Water. Cartilage is composed mostly of water, which decreases with age. About 85% of cartilage is water in young people. Cartilage in older people is about 70% water.

- Chondrocytes. These are the basic cartilage cells that are critical for joint health.

- Proteoglycans. These large molecules bond to water, which keeps high amounts of water in cartilage.

- Collagen. This essential protein in cartilage forms a mesh to give the joint support and flexibility. Collagen is the main protein found in all connective tissues of the body, including the muscles, ligaments, and tendons.

The combination of collagen mesh and water forms a strong and slippery pad in the joint. This pad (meniscus) cushions the ends of the bones in the joint during muscle movement.

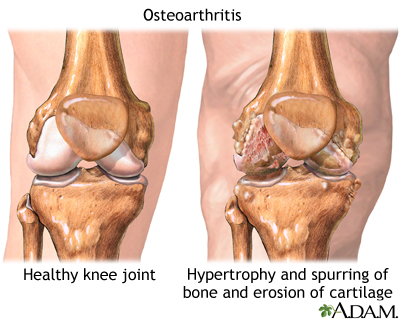

Osteoarthritis: The Disease Process

Deterioration of Cartilage. Osteoarthritis develops when cartilage in a joint deteriorates. The process is usually slow.

- In the early stages of disease, the surface of the cartilage becomes inflamed and swollen. The joint loses proteoglycan molecules and other tissues. This joint then begins to lose water. Fissures and pits appear in the cartilage.

- As the disease progresses and more tissue is lost, the cartilage starts to get hard. As a result, it becomes increasingly prone to damage from repetitive use and injury.

- Eventually, large amounts of cartilage are destroyed, leaving the ends of the bone within the joint unprotected.

Complicating the process are abnormalities in the bone around arthritic joints. As the body tries to repair damage to the cartilage, problems can develop:

- Clusters of damaged cells or fluid-filled cysts may form around the bony areas or near the fissures in the cartilage.

- Fluid pockets may also form within the bone marrow itself, causing swelling. The marrow, which runs up through the center of the bone, is rich in nerve fibers. As a result, these injuries can cause pain.

- Bone cells may respond to damage by multiplying, growing, and forming dense, misshapen plates around exposed areas.

- At the margins of the joint, the bone may produce outcroppings, on which new cartilage cells (chondrocytes) multiply and grow abnormally.

Location of Osteoarthritis

Unlike some other types of arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis is less likely to involve many joints around the body or migrate from around one joint to another. Rather, it affects one or a few joints, often joints that have received extra wear. Osteoarthritis affects joints differently depending on their location in the body.

- It is common in joints of the fingers, feet, knees, hips, and spine.

- It sometimes occurs in the wrist, elbows, shoulders, and jaw, but it is not as common in these locations.

Causes

The exact causes of osteoarthritis are not known. Scientists think that osteoarthritis likely develops from a combination of factors, including genetic susceptibility to joint injury.

Aging Cells

The body's ability to repair cartilage deteriorates with increasing age. Although osteoarthritis generally accompanies aging, osteoarthritic cartilage is chemically different from normal cartilage of the same age. As chondrocytes (the cells that make up cartilage) age, they lose their ability to make repairs and produce more cartilage. This process likely plays an important role in the development and progression of osteoarthritis.

Genetic Factors

Osteoarthritis tends to run in families. Genetic factors may be involved in about half of osteoarthritis cases in the hands and hips, and in a somewhat lower percentage of cases in the knee. Several genes that might contribute to an inherited risk are under investigation.

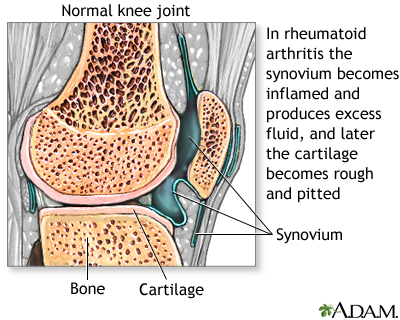

Inflammatory Response

The inflammatory response is an overreaction of the immune system to an injury or other assault in the body, such as an infection. This response causes specific immune factors, called cytokines, to gather in injured areas and cause inflammation and damage to body tissue and cells. The inflammatory response plays an important role in rheumatoid arthritis and other muscle and joint problems associated with autoimmune diseases.

Inflammation probably plays at most a minor role in the early stages of osteoarthritis and is more likely to be a result -- not a cause -- of the disease. However, inflammation may contribute to the progression of osteoarthritis and in its chronic nature. The effects of the inflammatory response in osteoarthritis are likely to be different, and less severe, than those in rheumatoid arthritis.

Joint Injury

Joint damage from injuries or recurrent stress to the joint is often the starting point in the osteoarthritis disease process. Osteoarthritis sometimes develops years after a single traumatic injury to or near a joint. Patients with knee injuries may be up to five times more likely to have osteoarthritis in the injured knee than those without injuries, and patients with hip injuries may be more than three times more likely to develop arthritis in the injured hip. Proper treatment of injuries, such as surgical repair of ligament tears in the knee with a strong rehabilitation approach, may help prevent the development of osteoarthritis.

Medical Conditions That Can Cause Osteoarthritis

Other causes of osteoarthritis include:

- Bleeding disorders that cause bleeding in the joint, such as hemophilia

- Disorders that block the blood supply near a joint, such as avascular necrosis

- Complications of persistent, inflammatory arthritic conditions, particularly chronic gout, pseudogout, or rheumatoid arthritis

- Conditions that cause iron build-up in the joints, such as hemochromatosis

- Anatomical abnormalities, such as mismatched surfaces on the joints, can become damaged over time. Legs of unequal length or skewed feet can cause jerky movement and may cause osteoarthritis.

Risk Factors

Age

Osteoarthritis can affect people of any age, but it is much more common in older people. It rarely occurs in people younger than age 40.

Gender

In people younger than 45, osteoarthritis occurs more frequently in men. After age 45, it develops more often in women. Some research suggests that women may also experience greater muscle and joint pain than men.

Obesity

Obesity increases the risk for osteoarthritis. It also worsens osteoarthritis once deterioration begins. This higher risk is due to increased weight on the joints.

Work and Leisure Factors

Because injuries can trigger the disease process, people whose work or leisure activities place them at risk for muscle and joint injuries may face a higher risk for osteoarthritis later on.

Occupational Risks. Certain occupations with repeated stressful motions (such as squatting or kneeling with heavy lifting) can contribute to the deterioration of cartilage. People with jobs that require kneeling or squatting for more than an hour a day are at high risk for knee osteoarthritis. Jobs that involve lifting, climbing stairs, or walking also pose some risk.

Exercise. There has been some question about the role of strenuous exercise in osteoarthritis. Sports that definitely pose a higher risk for osteoarthritis have repetitive or direct joint impact (such as football), joint twisting, or both (baseball pitching, soccer).

Regular and moderate exercise, however, is important for everyone and does not increase the risk for osteoarthritis. Recreational weight-bearing exercise (walking, jogging), done by middle-aged and elderly people, neither prevents osteoarthritis nor increases risk. Furthermore, many factors associated with a sedentary life (such as muscle weakness and obesity) are associated with a higher risk for osteoarthritis.

Symptoms

The pain of osteoarthritis typically begins gradually after age 40 and progresses slowly over many years. Younger people with the condition may have no symptoms at all. Osteoarthritis is commonly identified by the following symptoms:

- Stiffening after first awakening in the morning or after periods of inactivity later in the day. Stiffness (called gelling) resolves with activity, usually in about 20 minutes.

- Pain that worsens during activity and gets better during rest. This is the most common symptom of osteoarthritis. As the disease advances, the pain may occur even when the joint is at rest.

- Pain is generally described as aching, stiffness, and loss of mobility. The symptoms are often worse when resuming activities after periods of inactivity.

- The pain may be intermittent, with bad spells followed by periods of relative relief.

- Pain seems to increase in humid weather.

- Some people have muscle spasm and contractions in the tendons.

- Some people feel a grating sensation when the joint is used. Osteoarthritis in the knee may cause a crackling noise (called crepitus) when the affected knee is moved.

Symptoms by Location

Hand. Osteoarthritis of the hand occurs most often in older women and may be inherited within families. The following joints are most frequently affected:

- Distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint. The first joint below the fingertips is the most common location of osteoarthritis of the hand. These joints can develop bony growths known as Heberden's nodes.

- Carpometacarpal (CMC) joint. The joint at the base of the thumb, where the thumb joint connects with the wrist, is the second most common location.

- Proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint. The middle joints of the fingers can also develop osteoarthritis. These joints may develop small, solid lumps (nodules) known as Bouchard's nodes.

Osteoarthritis of the hand may predict the later development of osteoarthritis in the hip or knee.

Knee. Osteoarthritis is particularly debilitating in the weight-bearing joints of the knees. The meniscus, the cartilage pad between the joint formed by the thighbone and the shinbone, plays an important role in protecting this joint. It acts as a shock absorber. The joint is usually stable until the disease reaches an advanced stage when the knee becomes enlarged and swollen. Although painful, the arthritic knee usually retains reasonable flexibility.

Hips. About 1 in 4 people develop hip arthritis over the course of their lifetime. Being obese increases the risk. Osteoarthritis frequently strikes the weight-bearing joints in one or both hips. Pain develops slowly, usually in the groin and on the outside of the hips, or sometimes in the buttocks. The pain also may radiate to the knee, confusing the diagnosis. Those with osteoarthritis of the hip often have a restricted range of motion (particularly when trying to rotate the hip) and walk with a limp, because they slightly turn the affected leg to avoid pain.

Spine. Osteoarthritis may affect the cartilage in the disks that form cushions between the bones of the spine, the moving joints of the spine itself, or both. Osteoarthritis in any of these locations can cause pain, muscle spasms, and diminished mobility. In some cases, the nerves may become pinched, which also produces pain. Advanced disease may result in numbness and muscle weakness. Osteoarthritis of the spine is most troublesome when it occurs in the lower back or in the neck, where it can cause difficulty in swallowing.

Shoulder. Osteoarthritis is less common in the shoulder area than in other joints, but it may develop in the shoulder joint (the glenohumeral joint). In such cases, it is most often associated with a previous injury, and patients gradually develop pain and stiffness in the back of the shoulder. Osteoarthritis also can develop in the acromioclavicular (AC) joint, which is between the shoulder blade and the collarbone. However, it rarely causes symptoms in this location.

Diagnosis

Osteoarthritis is often visible in x-rays. Cartilage loss is suggested by certain characteristics of the images:

- The normal space between the bones in a joint is narrowed.

- There is an abnormal increase in bone density.

- Bony projections, cysts, or erosions are visible.

If the doctor suspects other conditions, or if the diagnosis is uncertain, additional tests are necessary.

Some people may have osteoarthritis even though it does not show up on an x-ray. Likewise, other people may have minimal symptoms even though an x-ray clearly shows they have osteoarthritis.

An MRI exam of an arthritic joint is generally not needed, unless the doctor suspects other causes of pain.

Physical Exam

The affected joint in patients with osteoarthritis will generally be tender to pressure right along the joint line. Joint movement may cause a crackling sound. The bones around the joints may feel larger than normal. The joint's range of motion is often reduced, and normal movement is often painful.

Blood Tests

Blood test results may help identify other types of arthritis besides osteoarthritis. Some examples include:

- Elevated levels of rheumatoid factor (specific antibodies in the blood) are usually found in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

- Abnormal results for tests such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, or "sed rate") and C-reactive protein (CRP) indicate inflammation, which may be caused by conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus

- Elevated uric acid levels in the blood may indicate gout

A number of other blood tests may help identify other rheumatologic illnesses.

Tests of the Synovial Fluid

If the diagnosis is uncertain or infection is suspected, a doctor may attempt to withdraw synovial fluid from the joint using a needle. There will not be enough fluid to withdraw if the joint is normal. If the doctor can withdraw fluid, problems are likely, and the fluid will be tested for factors that might confirm or rule out osteoarthritis:

- Cartilage cells in the fluid are signs of osteoarthritis.

- A high white blood cell count is a sign of infection, gout, pseudogout, or rheumatoid arthritis.

- Uric acid crystals in the fluid are an indication of gout.

- Other factors may be present that suggest different arthritic conditions, including Lyme disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

- In people with known osteoarthritis, researchers may look for certain factors in synovial fluid (sulfated glycosaminoglycan, keratin sulfate, and link protein) that can suggest a more or less severe condition.

Ruling Out Conditions with Similar Symptoms

Numerous conditions cause symptoms of joint aches and pains. Something as simple as sleeping on a bad mattress or as serious as cancer can mirror symptoms of osteoarthritis. Other problems that can cause aches and pains in the joints include physical injuries, infections, tendinitis, and poor circulation.

Osteoarthritis can generally be distinguished from other joint diseases by considering several factors together:

- Osteoarthritis usually occurs in older people and is located in only one or a few joints.

- The joints are less inflamed than in other arthritic conditions.

- Progression of pain is usually gradual.

Below are a few of the most common disorders that can be confused with, or may even accompany, osteoarthritis.

Rheumatoid Arthritis. Osteoarthritis can be confused at times with milder forms of rheumatoid arthritis, particularly when osteoarthritis affects multiple joints in the body. It normally occurs earlier in life than osteoarthritis, often striking people in their 30s and 40s. Rheumatoid arthritis affects many joints, and often occurs symmetrically on both sides of the body. People with rheumatoid arthritis generally have morning stiffness that lasts for at least an hour. (Stiffness from osteoarthritis usually clears up within half an hour.) Although osteoarthritis can occasionally cause swollen, red joints, this appearance is much more typical of rheumatoid arthritis and other types of inflammatory arthritis. In addition to blood tests, x-rays can help show differences between rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis.

Chondrocalcinosis (Pseudogout). Chondrocalcinosis (pseudogout syndrome) is a disease in which a certain type of calcium crystal known as CPPD (calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate) accumulates in the joints. This condition can accompany and even worsen osteoarthritis. Chondrocalcinosis is also called pseudogout or pseudo-osteoarthritis, the latter particularly when it affects the knees. A doctor can usually differentiate between the two disorders because chondrocalcinosis usually damages other joints (such as wrists, elbows, and shoulders) that are not normally affected by osteoarthritis.

Charcot's Joint. Charcot's joint occurs when an underlying disease, usually diabetes, causes nerve damage in the joint, which leads to swelling, bleeding, increased temperature, and changes in bone. There may be a loss of sensation that leads to an increased risk of injury from overuse.

Treatment

There is no cure for osteoarthritis, but there are many treatments that can relieve symptoms and significantly improve the quality of life.

The goals of osteoarthritis treatment are to reduce pain and improve joint function. Treatment approaches include:

- Lifestyle Changes. Lifestyle modifications and non-drug therapies are an important first step for treatment, and are used in combination with other treatment modalities. Lifestyle measures include exercise, weight loss, hot and cold therapies, pain management techniques, and the use of mechanical aids and assistive devices.

- Medications. For mild pain relief, doctors recommend acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and topical ointments. Patients with more severe pain may require stronger narcotic pain medication, corticosteroid injections, or visco-supplementation with injections of hyaluronic acid drugs.

- Surgery. For severe osteoarthritis that is not helped by other treatments, surgery such as joint replacement may be considered.

Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes can help reduce stress on affected joints.

Exercise

Joints need motion to stay healthy. Long periods of inactivity cause the arthritic joint to stiffen and the adjoining tissue to atrophy (waste away). A moderate exercise program that includes low-impact aerobics and power and strength training has benefits for patients with osteoarthritis, even if exercise does not slow down the disease progression. Exercise helps:

- Reduce stiffness and increase flexibility. It may also help improve the strength and elasticity of knee cartilage.

- Promote weight loss.

- Improve strength, which in turn improves balance and endurance.

- Reduce stress and improve feelings of well being, which helps patients cope with the emotional burden of pain.

Exercise especially helps patients with mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis in the hip or in the knee. Many patients who begin an aerobic or resistance exercise program report less disability and pain. They are better able to perform daily chores and remain more independent than their inactive peers. Older patients and those with medical problems should always check with their doctors before starting an exercise program.

Three types of exercise are best for people with osteoarthritis:

- Strengthening and resistance exercise

- Range-of-motion exercise

- Aerobic, or endurance, exercise

Strengthening and Resistance Exercise. Strengthening exercises include isometric exercises (pushing or pulling against static resistance). Isometric training builds muscle strength while burning fat, helps maintain bone density, and improves digestion. For patients with arthritis in the hip or knees, exercises that strengthen the muscles of the upper leg are important.

Range-of-Motion Exercise. These exercises increase the amount of movement in joints. In general, they are stretching exercises. The best examples are yoga and tai chi, which focus on flexibility, balance, and proper breathing.

Aerobic Exercise. Aerobic exercises help control weight and may reduce inflammation in some joints. Low-impact workouts also help stabilize and support the joint. Cycling and walking are beneficial, and swimming or exercising in water is highly recommended, for people with arthritis. (Patients with osteoarthritis should avoid high-impact sports, such as jogging, tennis, and racquetball if they cause pain.)

Physical and Occupational Therapy

In addition to exercise, treatment of muscles and joints by a physical therapist can be helpful. An occupational therapist can show you ways to more easily perform daily tasks of living without putting stress on your joints. Your therapist can recommend how to make changes in your workplace or work tasks to avoid repetitive or damaging motions.

Weight Reduction

Overweight patients with osteoarthritis can lessen the shock on their joints by losing weight. Knees, for example, sustain an impact three to five times the body weight when descending stairs. Losing 5 pounds of weight can eliminate 20 pounds of stress on the knee. The greater the weight loss, the greater the benefit.

Heat and Ice

Ice. When a joint is inflamed (particularly in the knee) applying ice for 20 - 30 minutes can be helpful. If an ice pack is not available, a package of frozen vegetables works just as well.

Heat Treatments. Soaking in a warm bath or applying a heating pad may help relieve stiffness and pain.

Mechanical Aids

A wide variety of devices are available to help support and protect joints. They include splints or braces, and shoe inserts or orthopedic shoes. A commonly used brace for knee osteoarthritis that involves only one side of the knee joint is called an offloading brace.

Assistive Devices

There are many different types of assisted devices that can help make your life easier in the home. Kitchen gadgets, such as jar openers, can assist with gripping and grabbing. Door-knob extenders and key turners are helpful for patients who have trouble turning their wrists. Bathrooms can be fitted with shower benches, grip bars, and raised toilet seats. An occupational therapist can advise you on choosing the right kinds of assistive devices.

Pain Management

Relaxation techniques such as guided imagery and breathing exercises may help some patients better cope with chronic pain.

Acupuncture, Transcutaneous Electric Nerve Stimulation (TENS), Therapeutic Ultrasound, and Massage

Some patients use acupuncture to reduce osteoarthritis pain. The technique is painless and involves the insertion of small fine needles at select points in the body. Some studies have found that acupuncture can help provide short-term pain relief for knee osteoarthritis.

Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) uses low-level electrical pulses to suppress pain. A variant (sometimes called percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, or PENS) applies these pulses through a small needle to acupuncture points. Some patients with knee osteoarthritis find this treatment helpful.

Ultrasound therapy uses high-energy sound waves to produce heat within the tissue, which may help reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and improve function. Therapeutic ultrasound is usually performed by a physical therapist using an ultrasound machine. The therapist applies gel to the affected area and moves a handheld ultrasound transducer over the joint. Some evidence suggests that therapeutic ultrasound may be beneficial for patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Massage therapy may also help provide short-term pain relief. It is important to work with an experienced massage therapist who understands how not to injure sensitive joint areas.

Herbs and Dietary Supplements

Glucosamine and Chondroitin. Glucosamine hydrochloride and chondroitin sulfate are natural substances that are part of the building blocks found in and around cartilage. For many years, researchers have been studying whether these dietary supplements really work for relieving osteoarthritis pain. Earlier studies suggested a potential benefit from these supplements.

However, several recent high-quality studies involving large numbers of patients have indicated that glucosamine and chondroitin, either alone or in combination, do not seem to work any better than a placebo for relieving symptoms of osteoarthritis. Based on these studies, the American College of Rheumatology does not recommend the use of these supplements. Some doctors suggest a trial period of three months to see if glucosamine and chondroitin work. If the patient does not experience any benefit, the supplements should be discontinued.

S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe). S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe, pronounced "Sammy") is a synthetic form of a natural byproduct of the amino acid methionine. It has been marketed as a remedy for arthritis, but scientific evidence supporting these claims is lacking.

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been several reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Medications

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) is the first choice for treating osteoarthritis pain. (Acetaminophen may be less effective than NSAIDs in reducing moderate-to-severe pain.) Because acetaminophen has fewer side effects, most doctors suggest trying this drug first, then switching to an NSAID if acetaminophen does not provide sufficient pain relief.

Side Effects. Acetaminophen is inexpensive and generally safe. It poses far less of a risk for gastrointestinal problems than NSAIDs.

It does have some adverse effects, however, and the daily dose should not exceed 4 grams (4,000 mg). Patients who take high doses of this drug for long periods are at risk for liver damage, particularly if they drink alcohol and do not eat regularly. Long-term, high-dose acetaminophen therapy may increase the risk for high blood pressure.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) block prostaglandins, the substances that dilate blood vessels and cause inflammation and pain. There are dozens of NSAIDs available:

- Over-the-counter NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic), naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn, generic), ketoprofen (Actron, Orudis KT, generic).

- Prescription NSAIDs include flurbiprofen (Ansaid, generic), diclofenac (Voltaren, Cataflam, Arthrotec, generic), tolmetin (Tolectin, generic), ketoprofen (Orudis, generic), nabumetone (Relafen, generic), indomethacin (Indocin, generic), meloxicam (Mobic, generic).

- Topical NSAIDs are gels, creams, or patches that are available either by prescription or over-the-counter. The American College of Rheumatology recommends the use of topical NSAIDs such as trolamine salicylate (Aspercreme, Myoflex, generic) for hand or knee osteoarthritis. (See Capsaicin section below for safety information about these products.)

Oral NSAIDs should be used only for a short period of time. Long-term use of NSAIDs does not delay the progression of osteoarthritis and can increase patients' risk of side effects.

Patients should use only the lowest effective dose because high dosages of NSAIDs can cause heart problems (such as increased blood pressure and risk of heart attack), kidney problems, and stomach bleeding. Because of these risks, the American College of Rheumatology recommends using topical NSAIDs in place of oral NSAIDs for patients 75 years and older.

Patients who take daily low-dose aspirin for heart protection should consider using an oral NSAID other than ibuprofen. Ibuprofen may make the aspirin less effective.

Patients who are at increased risk of stomach bleeding and ulcers should either switch to another type of pain reliever, or take the NSAID along with a proton-pump inhibitor drug, such as omeprazole (Prilosec, generic) or esomeprazole (Nexium), an H2 blocker such as famotidine (Pepcid, generic), or with the synthetic prostaglandin misoprostol (Cytotec, generic). (Misoprostol can cause miscarriage and should not be used by women who may be pregnant.) Some NSAIDs are available as combination pills; they include diclofenac/misoprostol (Arthrotec) and ibuprofen/famotidine (Duexis).

Capsaicin and Other Topical Products

Capsaicin is a component of hot red peppers and may bring pain relief when used as a skin cream (Zostrix, generic). This is the only skin preparation that does more than just mask pain or reduce it temporarily. Capsaicin seems to reduce a substance in the body, known as substance P, which contributes both to inflammation and the delivery of pain impulses from the central nervous system.

A small amount of capsaicin must be applied to the area of inflammation about four times a day. During the first few days of use, the patient will experience a warm, stinging sensation when the cream is applied. This sensation goes away, and pain relief usually begins within 1 - 2 weeks. The American College of Rheumatology recommends topical capsaicin for hand osteoarthritis but not for knee or hip osteoarthritis.

Topical over-the counter joint pain relievers that contain menthol, methyl salicylate, and (less commonly) capsaicin may in rare cases cause chemical burns. Menthol and methyl salicylate products are sold under brand names such as Bengay, Flexall, Icy Hot, and Mentholatum. Products that contain capsaicin include Capzasin as well as Zostrix. The risks appear more severe for combination products that contain higher doses of both menthol (greater than 3%) and methyl salicylate (greater than 10%). The FDA recommends:

- Don’t apply these products to damaged or irritated skin

- Don’t apply bandages, heating pads, or hot water bottles to areas treated with these products

- If you see any signs of blisters or burns, stop using the product and seek medical attention.

These warnings also apply to the topical NSAID products that contain trolamine salicylate (see NSAIDs section above).

COX-2 Inhibitors (Coxibs)

Coxibs inhibit an inflammation-promoting enzyme called COX-2. This drug class was initially thought to provide benefits equal to NSAIDs but cause less gastrointestinal distress. However, following numerous reports of cardiovascular events, as well as skin rashes and other adverse effects, most COX-2 inhibitors were withdrawn from the market. Celecoxib (Celebrex) is still available, but patients should discuss with their doctors whether this drug is appropriate and safe for them.

Duloxetine (Cymbalta)

Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressant that is used to treat depression, anxiety disorders, diabetic nerve pain, and fibromyalgia. In 2010, the FDA approved duloxetine for treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain associated with osteoarthritis.

Tramadol

Tramadol (Ultram, generic) is a pain reliever that has been used as an alternative to opioids. It has opioid-like properties but is not as addictive. (Dependence and abuse have been reported, however.) It can cause nausea but does not cause severe gastrointestinal problems, as NSAIDs can. Some patients experience severe itching. A combination of tramadol and acetaminophen (Ultracet, generic) is available.

Narcotics

Narcotics, pain-relieving and sleep-inducing drugs that act on the central nervous system, are the most powerful medications available for the management of moderate-to-severe pain. There are two types of narcotics:

- Opiates, which are derived from natural opium (morphine and codeine)

- Opioids, which are synthetic drugs. They include oxycodone (such as Percodan, Percocet, Roxicodone, OxyContin, generic), hydrocodone (Vicodin, generic), oxymorphone (Numorphan, Opana), and fentanyl (Duragesic, generic)

Although the use of narcotics for arthritic pain is controversial, they may have a place in osteoarthritis treatment when milder drugs are not effective or appropriate. These drugs can be highly addictive, and should be prescribed at the lowest possible effective dose.

Common side effects include anxiety, constipation, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, paranoia, urinary retention, restlessness, and labored or slow breathing.

Corticosteroid Injections

When pain becomes a major problem and less potent pain relievers are ineffective, doctors may try corticosteroid (steroid) injections, usually by giving the patient a shot in their joint every 3 months. Corticosteroid shots are useful only if inflammation is present in the joint. Relief from pain and inflammation is of short duration, and this treatment is rarely used for chronic osteoarthritis. These drugs may not be as effective for women as they are for men. The American College of Rheumatology does not recommend these injections for hand osteoarthritis.

Patients are usually advised not to have more than two or three injections a year, since there is some concern that repeated injections over the long term may be harmful. Because long-term use of corticosteroids has many potentially serious side effects, steroid medications are never given by mouth or systemically for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Hyaluronic Acid Injections (Viscosupplementation)

Injections of hyaluronic acid (such as Hyalgan, Synvisc, Artzal, and Nuflexxa) into the joint -- a procedure called viscosupplementation -- may provide pain relief for knee osteoarthritis. Relief usually lasts several months. The most common side effects, pain at the injection site and knee pain and swelling, are usually mild and temporary. Some studies report that these injections provide only very modest pain relief at best.

Surgery

Different surgical procedures are available as a final measure to relieve pain and increase function in patients with osteoarthritis. Certain surgical procedures can help relieve pain if medications fail. Even with these procedures, however, joint replacement may still be needed later on.

Arthroscopy and Debridement

Arthroscopy is performed to clean out bone and cartilage fragments (debridement) that, in theory at least, may cause pain and inflammation. It is also sometimes used to diagnose osteoarthritis. In this procedure, the surgeon makes a small incision and inserts the arthroscope, a pencil-width fiber-optic instrument that contains a light and magnifying lens. The arthroscope is attached to a miniature television camera that allows the surgeon to see the inside of the joint.

Research and debate continues on whether arthroscopy provides true benefits for those with osteoarthritis and, if so, which patients may benefit the most from it. Arthroscopy is most likely to benefit people with mild-to-moderate osteoarthritis who have evidence of bone and cartilage fragments in the joint, or patients whose joints lock or catch with movement.

Joint Replacement (Arthroplasty)

When osteoarthritis becomes so severe that pain and immobility make normal functioning impossible, many people become candidates for artificial (prosthetic) joint implants using a procedure called arthroplasty. Hip replacement is the most established and successful replacement procedure, followed by knee replacement. Other joint surgeries (such as shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers) are less common, and some arthritic joints (in the spine, for instance) cannot yet be treated in this manner. When two joints, such as both knees, need to be replaced, having the operations done sequentially rather than at the same time may result in fewer complications.

Candidates. The primary indications for surgery are pain and significant limitations of movement, including walking, that cannot be treated by less invasive therapies.

Patients who may not be good candidates are those with the following conditions:

- Severe neurologic, emotional, or mental disorders

- Severe osteoporosis

- Other chronic medical conditions

- Obesity

Surgeons often prefer to delay prosthetic implantation in younger patients, because implants wear out and the patient will need at least one revision procedure later on. Newer, longer-lasting materials, however, may help reduce the rate of revision operations.

Elderly patients with poorly controlled osteoarthritis often do very well after joint replacement surgery. While full recovery may take older patients longer to achieve than younger people, the long-term outcome of the surgery is usually excellent, and can lead to significant improvements in pain and quality of life.

Complications. Complications can occur, and, although uncommon, some can be life threatening. In addition to blood loss and infection, deep blood clots in the legs (deep venous thrombosis) are a serious potential complication. These clots can potentially travel to the lungs (pulmonary embolism) and pose a risk for death. Patients who are overweight are at higher than average risk for blood clots.

Recovery and Rehabilitation. Aside from the surgeon's skill and the patient's underlying condition, the success rate depends on the kind and degree of activity the joint receives following replacement surgery. Physical therapy takes about 6 weeks to rebuild adjoining muscle and strengthen surrounding ligaments. Patients typically experience considerable pain during this time.

While many patients find that joint replacement eventually provides pain relief and restores some mobility, they need time to adjust to the artificial joint.

Limitations after hip surgery include:

- Usually patients with new hips are able to walk several miles a day and climb stairs, but they cannot run.

- Prosthetic hips should not be flexed beyond 90 degrees, so patients must learn new ways to perform activities requiring bending down (like tying a shoe).

Limitations after knee surgery include:

- Walking distance improves after knee replacement surgery, but patients still cannot run.

- Artificial knee joints generally have a limited range of motion of just 110 degrees and stair climbing may remain difficult.

Minimally Invasive Arthroplasty. Surgeons are exploring a variety of new techniques for a “minimally invasive” approach to knee and hip arthroplasty. They include using a shorter incision, and new types of smaller specialized instruments. The goal is to give the patient a shorter recovery time and less postoperative pain. However, minimally invasive arthroplasty is still in its early stages. At this time, there is no consensus on which minimally invasive technique works best, or if it actually achieves any additional benefits beyond the recovery period.

Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (also called unicondylar knee arthroplasty) may be a useful procedure in cases of limited knee damage. It is recommended for relatively sedentary patients who are 60 years or older and not obese. It may relieve pain and delay the need for a total knee replacement. The procedure involves a small incision and insertion of small implants. It retains important knee ligaments, which preserve more movement than a total knee replacement.

Hip Resurfacing. Hip resurfacing is a surgical alternative to total hip replacement. It involves scraping the surfaces of the hip joint and femur and placing a metal cap over the bone. The procedure preserves much of the bone, so that a standard hip replacement can be done years later if needed. It may provide more stability, a faster recovery, and greater range of motion, making it a potentially good option for young, physically active patients.

Revision Arthroplasty. A repair procedure called arthroplasty revision may be used in cases where the original transplant fails. The specific procedure depends on whether the bone defects that occurred are contained or uncontained.

- Contained defects can be repaired with small bone grafts, the use of cement, or oversized cementless implants as required.

- Uncontained defects are more severe and may require a large bone graft or specially constructed implants to restore bone.

If a second arthroplasty is required, the potential for complications is magnified: more bone is cut, more blood is lost, and the operation takes longer. Patients are also generally older and more vulnerable to complications.

Realigning Bones (Osteotomy)

Osteotomy is a surgical procedure used to realign bone and cartilage and reposition the joint. If only a certain section (the medial compartment) of the knee is damaged and deformed by osteoarthritis, the surgeon may choose to perform an osteotomy:

- The surgeon opens the knee.

- The surgeon performs a debridement (removal of damaged tissue) in the joint to eliminate the loose or torn fragments that are causing pain and inflammation.

- The bone is then reshaped to remove the deformity.

- The procedure may ease symptoms and slow disease progression. It is best used in heavier adults who are younger than age 60 years.

Hemicallotasis. Hemicallotasis is a procedure for the knee that may be a less invasive alternative to osteotomy. The surgeon attaches the knee with pins to an external frame-like device that lengthens the deformed part of the knee over several weeks. The patient is mobile during this period. Infections at the pin site are the most common complications.

Fusing Bones (Arthrodesis)

If the affected joint cannot be replaced, surgeons can perform a procedure called arthrodesis that eliminates pain by fusing the bones together. The patient must understand, however, that fusing the bones makes movement of the joint impossible. Bone fusion is most often done in the spine and in the small joints of the hands and feet.

Resources

- www.rheumatology.org -- American College of Rheumatology

- www.arthritis.org -- Arthritis Foundation

- www.niams.nih.gov -- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- www.aaos.org -- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

References

Bannuru RR, Natov NS, Obadan IE, Price LL, Schmid CH, McAlindon TE. Therapeutic trajectory of hyaluronic acid versus corticosteroids in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Dec 15;61(12):1704-11.

Brouwer RW, Raaij van TM, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Osteotomy for treating knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD004019.

Cepeda MS, Camargo F, et al. Tramadol for osteoarthritis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(3):543-555.

Das A, Neher JO, Safranek S. Clinical inquiries. Do hyaluronic acid injections relieve OA knee pain? J Fam Pract. 2009 May;58(5):281c-e.

Fransen M, McConnell S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Oct 8;(4):CD004376.

Hamel MB, Toth M, Legedza A, et al. Joint replacement surgery in elderly patients with severe osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: decision making, postoperative recovery, and clinical outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1430-1440.

Hernández-Molina G, Reichenbach S, Zhang B, Lavalley M, Felson DT. Effect of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis pain: results of a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Sep 15;59(9):1221-8.

Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, Benkhalti M, Guyatt G, McGowan J, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip,

and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Apr;64(4):455-74.

Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, Freehill MQ, Stanwood W, Wiater JM, et al. The treatment of glenohumeral joint osteoarthritis: guideline and evidence report. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. 2009 Dec 5; v1.0.

Lane NE. Clinical practice. Osteoarthritis of the hip. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(14): 1413-1421.

Lange AK, Vanwanseele B, Fiatarone Singh MA. Strength training for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Oct 15;59(10):1488-94.

Laupattarakasem W, Laopaiboon M, Laupattarakasem P, et al. Arthroscopic debridement for knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD005118.

Leopold SS. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 23;360(17):1749-58.

Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, Lao L, Yoo J, Wieland S, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;(1):CD001977.

Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jun 11. [Epub ahead of print]

Rutjes AW, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S, Jüni P. S-Adenosylmethionine for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Oct 7;(4):CD007321.

Rutjes AW, Nüesch E, Sterchi R, Jüni P. Therapeutic ultrasound for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;(1):CD003132.

Sinusas K. Osteoarthritis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Jan 1;85(1):49-56.

Wandel S, Jüni P, Tendal B, Nüesch E, Villiger PM, Welton NJ, et al. Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010 Sep 16;341:c4675. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4675.

|

Review Date:

9/25/2012 Reviewed By: Reviewed by: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |